Have you ever wondered how come search engines likely guess what you are looking for when you enter a given query? Don’t worry, the machines don’t know how to read our minds 😉 . What enables such adaptation is called search intent, and it entirely relies on the phrases internet users use to express their needs. In this article, you’ll learn more about this concept and how to use search intent in the content creation process!

To give it an example, if you put something related to the Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh in the search engine of your choice, how does it know if you want to:

A) read his biography,

B) check where you can see his art (in which museums),

C) learn how to paint using his remarkable technique,

D) buy a replica of one of his paintings?

Well, it depends on the additional words you’ll use. You’ll get to know his story by writing just “van Gogh” or “van Gogh life”. If you want the B scenario to come true, you’ll most likely use a phrase such as “van Gogh paintings” or “where to see van Gogh”. To learn how to paint like him, you’ll add “technique” to his name. And finally, to buy a poster with his art “lookalike”, you’ll simply enter the name of a specific painting you’re interested in. That’s where the magic happens!

Search intent is the intention of a person looking for something online. It’s also the cause of internet search engines’ existence. They obviously want to make sure that what they display to users meets their needs. This is why digital content created with search intent in mind is very likely to rank higher in search results.

Search engines constantly improve their mechanisms to provide their users with the best-suited results possible. For example, Google created special algorithms (Hummingbird in 2013, RankBrain in 2015, and BERT in 2018) to better understand words, their meaning and contexts, which led to a superior interpretation of queries. The engines also consider things like dwell time (a time that passes from entering a website listed in search results and getting back there to keep on looking for an answer to the query) and bounce rate (percentage of users not passing to other pages of the same website). Short dwell time and a high bounce rate are clear signals that a given result doesn’t meet users’ needs for the entered phrase.

Search intent types

There are three basic reasons why a person may be looking for something online. The search intent types are based on the searcher’s intention, i.e. what they need in a specific situation:

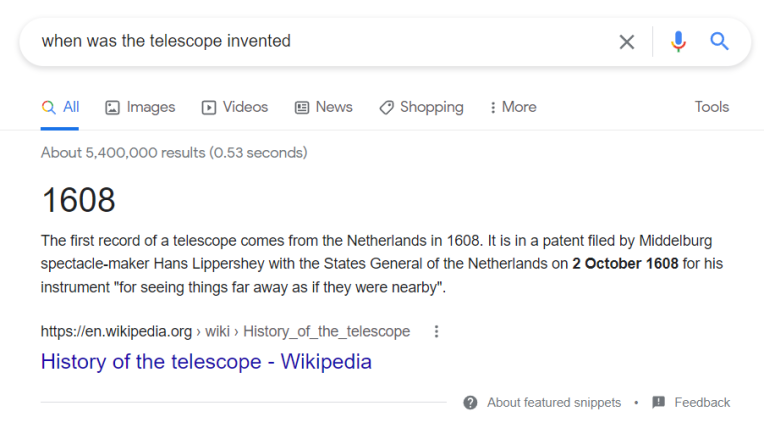

- Know – informational intent – the user is looking for specific information on a given subject, e.g.: “when was the telescope invented”;

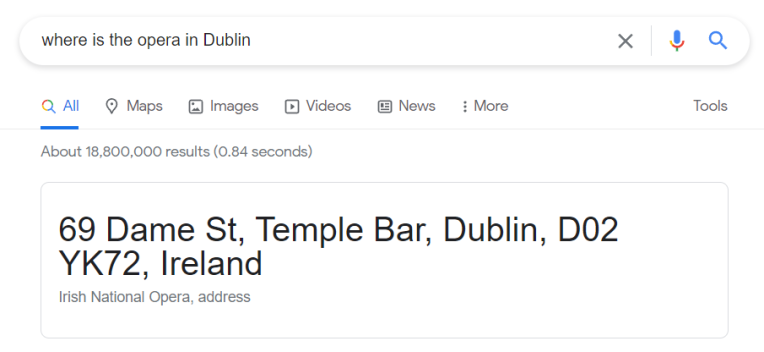

- Go – navigational intent – the user wants to get somewhere (in the offline or online world), e.g.: “where is the opera in Dublin”;

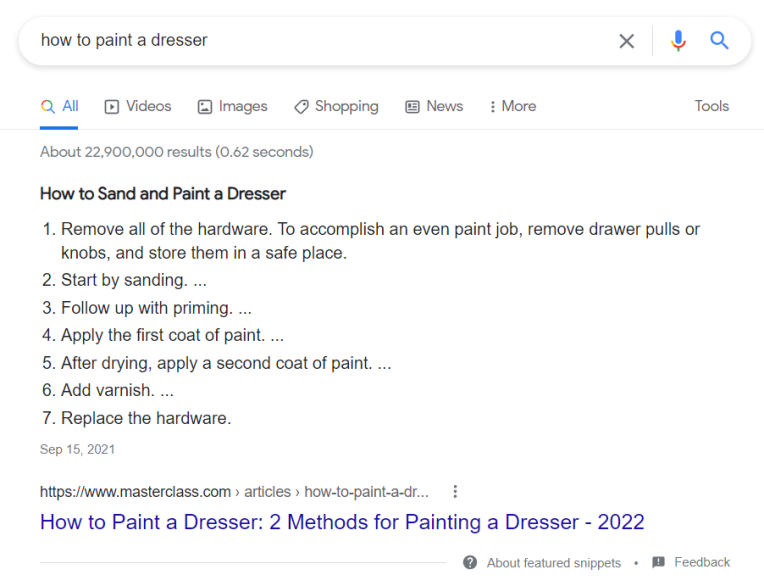

- Do – transactional or skill intent – the user considers making a purchase or tries to learn how to do something, e.g.: “how to paint a dresser”.

Did you notice how the search engine (in this case, Google) distinguishes pages containing the best answer to the entered query? It doesn’t only take a high place in its results, but it’s also presented in a very approachable way. That’s how the user easily finds what she or he needs, and the best-fitting website for that question gets the possibility to gain massive user traffic. It’s a win-win!

Google Micro Moments

Based on the above-described search intent types, Google developed its own division that also relies on basic users’ needs. Here’s how they describe the four so-called Micro-Moments:

In these moments, consumers want what they want, when they want it – and they’re drawn to brands that deliver on their needs.

- I want to know – informational intent equivalent;

- I want to go – navigational intent equivalent;

- I want to do – skill intent equivalent;

- I want to buy – transactional intent equivalent.

Why should publishers reckon with search intent?

Knowing for what purpose your target audience might be looking for your content will let you adjust it to be found easily. The first thing you can consider is the proper usage of supplementary words. It’s particularly helpful when creating titles: for example, for the know intent type, people may use interrogative pronouns “who”, “when”, and “what”; in the case of go intent, they’ll most likely add “where” to their query; and for do intent it’ll be “how” or “which” (if they’re trying to find a ranking to help them choose what to buy); and when the users already know what they want to purchase, they’ll probably just use the name of this item (or accompany it with “buy”).

You can also see which other creators’ articles rank high in search results for the phrases your users would use when having a particular search intent. This way, you’ll see what kind of content the search engines consider best fitting to a given query. It’ll let you better understand your audience’s needs and create a content structure that would be well interpreted by algorithms. For instance, if you create a guide on how to do something, marking each step with a number will allow search engines to create snippets that are really helpful and attractive for users and will make you rank higher.

Defining your target audience’s search intent also lets you reduce your content’s competition. Imagine preparing an article on how someone can change a car’s tires on their own. If you entitle it “tire change”, you’ll not only compete for a high ranking position with other publishers creating a similar guide, but also with mechanical services offering such service. All you need to do in order to change that is to weave “how to” into your title.

Summing up

Bear in mind that there’s always an intention behind a person looking for something on the internet. Knowing what it is, makes you able to respond to their query appropriately and enhances your content chances of being considered useful by the search engines. It also makes it much more probable for your content to be found by the users. Therefore, adjust your titles, descriptions, and overall content structure to your audience’s possible search intent. Imagine them as a group of listeners taking part in your lecture – you just have to know why they came here in order to make your performance appealing!